Stan Sudol is a Toronto-based communications consultant and mining columnist. Stan.sudol@republicofmining.com

A much shorter version of this article appears in the September, 2011 issue of the Northern Miner’s Mining Markets: A Resource for Investors magazine.

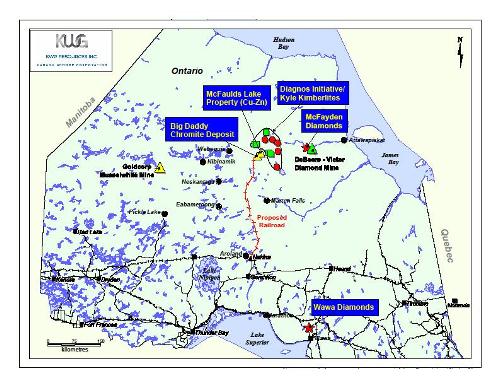

A fever is spreading throughout northern Ontario, from the eastern districts adjacent Quebec to the far reaches of the northwest right up to the Manitoba border. This raging malaise is caused by a metal that has captured mankind’s attention from the dawn of time. I am referring to “gold fever” and many in northern Ontario – a vast northern territory, which is almost equal to Germany, United Kingdon, Greece and Ireland combined – are thoroughly infected or obsessed over this beautiful precious metal.

Historically, Ontario’s gold mining industry has played a major role in the settlement of the province’s northern regions and along with the Cobalt silver boom and further gold and base metal discoveries in northwestern Quebec were primarily responsible for the establishment of Toronto as today’s mine financing capital of the world.

The many gold mines that came into production during the Depression of the 1930s made a vital contribution to keeping the province solvent and with over a century of experience building many underground mines helped solidify Ontario’s hard-rock mining expertise that is well respected globally.

However, northern Ontario’s gold rushes have always seemed to play second-fiddle to the legendary Klondike in the Yukon, aided by famous writers like Jack London, Robert W. Service – of the Cremation of Sam McGee fame – and Canadian literary icon, Pierre Berton. At it’s peak, the Klondike gold rush only lasted for a few years – 1896-99 – and produced a miserly 12.5 million ounces of gold. “Chump change” compared to northern Ontario’s four major gold rushes and a number of smaller gold districts, most of which are still producing the precious metal today.

Considering the record setting price of gold, moving upwards almost daily, the political stability of northern Ontario and its strong world-class mining infrastructure versus lesser developed countries like Tanzania, Guatemala or Papua New Guinea, exploration in all current and former gold mining camps is booming.