The Globe and Mail is Canada’s national newspaper with the second largest broadsheet circulation in the country. It has enormous influence on Canada’s political and business elite.

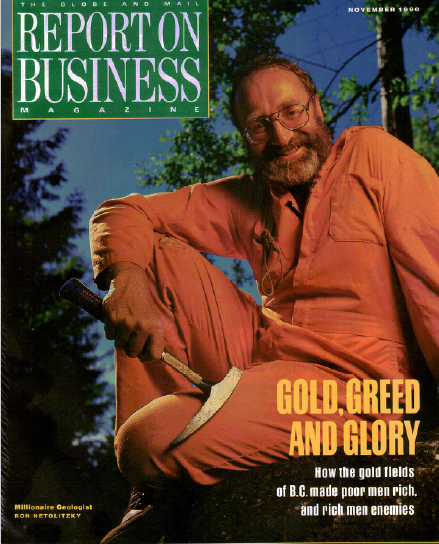

High in the Skeena Mountains of northern British Columbia, Ron Netolitzky stands nervously atop a 90-metre bluff. Netolitsky is a geologist from the Prairies, utterly out of his element. “I’m afraid of a 10-foot stepladder,” he confides. From the grassy peak, he surveys the remote river valleys and snow-capped mountains that lie 200 kilometers south of the Yukon border.

The only movement in sight is a heard of mountain goats on the next ridge. Summoning his courage, Netolitzky pulls a hammer out of his pocket and cautiously skates down the rust-coloured slope towards his latest mineral discovery.

To the untrained eye, all the rocks sliding underfoot look the same. But partway down, Netolitzky stops, cracks open a chunk of porphyry with his hammer and spits on the inside. After rubbing the sample clean, he wipes his hand on the same pair of ripped, orange coveralls he’s been wearing in the bush for eight years. “There,” he says, studing the core with an eyeglass. “That’s copper. And where there’s copper, you stand a good chance of finding gold.”

Put that way, it all sounds so simple. But the Skeenas, alongside the Alaska Panhandle, have been a formidable shield against prospectors and miners. The surrounding 20,000 square kilometres is known invitingly as the Golden Triangle, but it is an inhospitable place of dense spuce forest, stubborn glaciers, thick muskeg and towering cliffs formed 200 million years ago.

Read more