To order a copy of “J.P. BICKELL: The Life, the Leafs, and the Legacy”: https://www.dundurn.com/books/JP-Bickell

Jason Wilson is a bestselling Canadian author, a two-time Juno Awards Nominee, and an Adjunct Professor of History at the University of Guelph. He has performed and recorded with UB40, Ron Sexsmith, Pee Wee Ellis, and Dave Swarbrick. Jason lives in Stouffville, Ontario.

Kevin Shea is a renowned hockey historian and bestselling author of fourteen hockey books. He is the Editor of Publications and Online Features for the Hockey Hall of Fame, a member of the Toronto Maple Leafs Historical Committee, and a founding member of Road Hockey to Conquer Cancer. Kevin lives in Toronto.

Graham MacLachlan is a relative of J.P. Bickell who has an extensive business background in international trade that is equalled by his involvement in hockey in the IIHF, the WHL, Hockey Canada, Hockey Alberta, and Hockey Calgary. Graham lives in Calgary, Alberta.

OVERVIEW

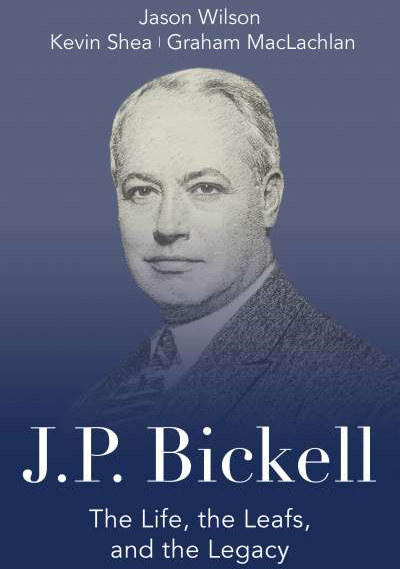

He stayed out of the spotlight, but Leafs fans know J.P. Bickell cast a long shadow.

A self-made mining magnate and the man who kept the Maple Leafs in Toronto and financed Maple Leaf Gardens, J.P. Bickell lived an extraordinary and purposeful life. As one of the most important industrialists in Canadian history, Bickell left his mark on communities across the nation. He was a cornerstone of the Toronto Maple Leafs, which awards the J.P. Bickell Memorial Award to recognize outstanding service to the organization.

Bickell’s story is also tied up with some of the most famous Canadians of his day, including Mitchell Hepburn, Roy Thomson, and Conn Smythe. Through his charitable foundation, he has been a key benefactor of the Hospital for Sick Children, and his legacy continues to transform Toronto. Yet, though Bickell was so important both to Toronto and the Maple Leafs, the story of his incredible life is today largely obscure. This book sets the record straight, presenting the definitive story of his rise to prominence and his lasting legacy — on the ice and off.

Excerpt

The Bickell-Ennis tandem would write mining history in Canada — that is, after a long, precarious prelude. To be sure, the assays were sparse to begin with and development was weighed down with a host of difficulties. Bankruptcy loomed at several junctures. And Bickell was still somewhat handcuffed by the board that had the marks of the New York group imprinted all over it. The determined Bickell-Ennis team was not put off, however. Bickell, as Clary Dixon observed, was willing to learn from Ennis’s mining acumen: “Bickell always listened to Dick Ennis, and Dick knew his stuff.”

Trusting in his manager’s multifarious skill sets, Bickell busied himself with the business of buying up the other parts of Pearl Lake. The accumulation of property did not immediately translate into success, as Dixon confessed:

“The early days were something, a regular circus. The first stock was sold in the States, you know, at about $2 a share. Damned company was reorganized and stockholders cut down 80 per cent. It was a case of tough titty and no teeth. Company always in debt.”

In the end, it was ingenuity, gumption, and guile that kept the company going. In what might very well be a case of romance lusting after fact, Ennis is said to have averted a crisis by rushing a still-hot gold brick to the bank to meet the company’s payroll and to save the friendly bank manager embarrassment after he’d put his neck on the line for Ennis and company.

Dixon also recalled how Ennis would “hide underground whenever creditors came to the mine howling about unpaid bills.” When the miners went out on strike in 1913, the writing appeared to be on the wall for McIntyre Porcupine. The company tried to sell stock to Hollinger at a paltry thirty-five cents, but even this price was considered too high. These were despairing times.

Bickell, as director, came to the rescue. Essentially, Bickell kept McIntyre Porcupine afloat on his own dime. In 1913 Bickell put out a $250,000 bond issue to finance a three-hundred-ton mill. Yet, even with a promised bonus of one thousand free shares with every $1,000 bond, no one seemed interested in investing.

Bickell and Ennis were, however, able to persuade some of the machinery companies into taking bonds for equipment. Likewise, Ennis was also able to persuade the mine’s doctor to take 550 shares in the company in lieu of his cash fee. Dixon aptly described the company’s anxious situation: “McIntyre was the biggest joke in Porcupine.” But it was no joke for Bickell, who remained resolute. J.P. loaned the company money to meet the most pressing bills while personally guaranteeing notes to others. This included wages and taxes.

Bickell had been elected a director when Freeman, the man who had once negotiated on Bickell’s behalf, resigned. It was no secret that J.P. did not appreciate how Freeman had been doing business. Inexplicably, at least as far as Bickell was concerned, Freeman, who was then out on bail, was reinstated as president of McIntyre by the board in April 1914. As historian Philip Smith surmised:

“Bickell was certainly even more displeased a few months later when a board meeting at which he was not present agreed to redeem, or buy back, Freeman’s holding of McIntyre Porcupine bonds. Freeman agreed to part with the bonds at thirty per cent below their face value, but the board’s action was clearly illegal: the holders of a company’s bonds have first claim on its assets, and Freeman had no right to get his money out before all the other bond-holders could be paid off.”

This may have been the straw that broke the camel’s back. Bickell was determined now to take charge of McIntyre Porcupine and to squeeze Freeman and his crew out of the scene altogether. On May 5, 1915, Freeman stepped aside, explaining to the shareholders that the company no longer needed his services. That same day, Colonel Alexander M. Hay replaced Freeman as president, and Sir Henry Pellatt (of Casa Loma fame) was named vice-president. From this point forward, it was effectively Bickell who built the company into one of the greatest mining companies in Canada and the world.

In 1915, the McIntyre Extension Company was formed. An additional 120 acres were acquired from the Pearl Lake Company. At the same time, the McIntyre Jupiter Company took over the holdings of the Jupiter mine. In 1916, the three companies, McIntyre Porcupine, McIntyre Extension, and McIntyre Jupiter, were amalgamated under Colonel Hay’s presidency. Hay, along with W.J. Sheppard and J.B. Tudhope, were all prominent mining men brought in by Bickell to bring together the disparate pieces around Pearl Lake. The Colonel served as McIntyre Porcupine’s president from April 1915 until January 1917. He died only one day before McIntyre declared its first dividend.

More happily, the mine’s shaft began to tap into the more favourable greenstone area. The ore, albeit slowly, began to improve. And as the grades of gold improved, the McIntyre Porcupine, thanks to Bickell’s stewardship, had successfully negotiated those early turbulent waters.

Ennis too, was crucial to the company’s survival, and was rightly credited with the rapid development of the mine below the so-called five-hundred-foot horizon (the point when a mine becomes a going concern). Indeed, by 1916 all liabilities had been discharged, and the first dividend was ready to be paid out in 1917. McIntyre Porcupine could now count itself within Porcupine’s “Big Three.” Bickell had seen the bleakest days of the company through and would remain as chairman of the board until his death.

Reproduced with permission of Dundurn Press. https://www.dundurn.com/