Notwithstanding the historical hype of the Klondike Gold Rush in Canadian society, the two most important mining events in our history are the discoveries of the Sudbury nickel mines in 1883 and the Cobalt silver boom of 1903.

Both were the result of railroads – the construction of the Canadian Pacific to British Columbia in Sudbury’s case and the building of the provincial Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway, going through Cobalt, which was for the colonization of northern Ontario.

But the similarities end there. Sudbury was built with U.S. capital and strategic technology. Cobalt was largely built and significantly financed by Canadian business and was the start of Canada’s global reputation as mine finders and builders. The two camps had much overlap but were also very distinct in their own rights.

Ohio-born businessman Samual J. Ritchie was the driving force who really started mining production in the Sudbury Basin with the founding of the Canadian Copper Company in 1886. A subsequent merger in 1902 with the New Jersey-based Orford Copper Company, which had the vital technology to separate the nickel from the copper in Sudbury’s complex ore, lead to the creation of the legendary International Nickel Company. (INCO)

In 1901, Thomas Edison had come to Sudbury hoping to develop a nickel deposit that could be used for his electrical equipment in Falconbridge township but abandoned the project due to quicksand.

Thayer Lindsay eventually developed those claims and formed Falconbridge Nickel Mines, the second largest producer of nickel in the western world and would begin a local rivalry with Inco that endured until both were taken over.

Both Inco Limited and Falconbridge Limited, founded in 1928 would leverage their Sudbury basin mines to become corporate giants with global operations.

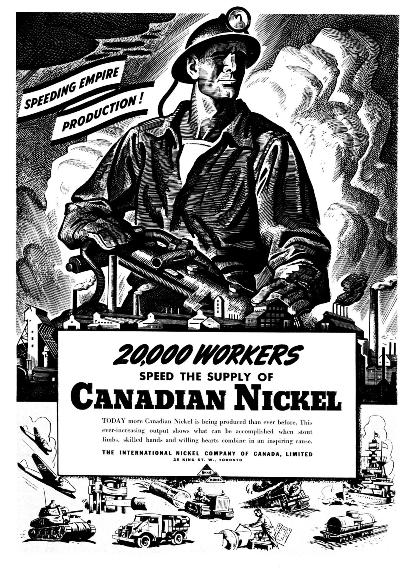

Nickel-steel alloys became the perfect metal for war used in a wide variety of ways – due to its steel strengthening and corrosive and heat resistant attributes that have no substitutes – including the construction of the feared dreadnought ships of the First World War, tanks, ordnance and the mighty B-29 bombers that were instrumental for our success during World War Two.

CEO Robert Stanley guided Inco for much of its first 50 years and basically saved the company when nickel markets crashed after the end of the First World War by finding many peace time uses. Under his leadership, sales of nickel increased from 13 million pounds in 1921 to 241 million in 1951, the year he passed away.

In the late 1920s as tensions between Britain and the U.S. deteriorated, the American military had prepared a Joint Army and Navy Basic War Plan to invade Canada if war ever broke out with the U.K. It was updated in 1935!

The most interesting part of the plan is the emphasis on capturing Sudbury’s vital nickel deposits which are mentioned several times throughout the plan. The invasion route, through Sault Ste. Marie, was focused on quickly securing the Sudbury Basin. The War Plan Red stated, “Unless nickel can be obtained from the Sudbury mines, a serious shortage in that important war-making material will develop in Blue within a few months after the war begins.”

For much of the 20th century, Sudbury was a key source of this strategic material supplying upwards to 90% of global demand at various times. It could have been easily described as the “Saudi Arabia of nickel”!

A 1954 U.S. Department of Defense report stated that nickel was “the closest to being a true ‘war metal.’ It deserves first priority among materials receiving conservation attention.” There had always been a close association between senior Inco management and the American military-industrial complex for most of the 20th century.

The American military stockpiled nickel during the 1950s and 1960s as it was in constant short supply due to a booming U.S. economy, rebuilding war-torn Europe, the Korean War and the ensuing Cold War between America and the U.S.S.R. (known as Russia today) which caused an enormous build-up of military capacity on both sides. Sudbury literally “exploded” with mining activity. The population in 1951 was 42,410 and practically doubled to 80,120 by 1961.

In addition, the largest single population increase in the history of Northern Ontario also occurred during that decade due a period of unprecedented economic prosperity. The boom, mostly in the mining sector, pushed the population from 536,000 in 1951 to 722,000 in 1961.

During the 1950s, the U.S. government gave Falconbridge/Glencore a $40 million subsidy – roughly an astonishing $390 million in 2020 dollars – to help develop one their Sudbury nickel mines and ensure diversity of supply. At the time, INCO supplied almost 80 to 90 per cent of the west’s supply of nickel and the military were terrified of being so dependent on one key supplier.

Thousands of single men with good paychecks made Sudbury a magnet for con artists, prostitutes, gambling, illicit booze and drugs. As Maclean’s journalist Don Delaplante wrote in a 1951 profile of the city, “Sudbury is a lusty, chest-thumping, nonsleeping and rather wicked melting pot of both mankind and ore…” The old Borgia Street in the central core – long gone with urban renewal – was reputed to be among the toughest neighbourhoods in Canada.

Nickel alloys also played a key in NASA’s efforts to land men on the moon in 1969, as those metallic attributes made it possible for the astronauts to withstand the harsh conditions of outer space. Growing up in Sudbury during the 1960s/1970s, both Inco and Falconbridge would use the space race as a terrific marketing tool and I recall being genuinely proud of the contributions of my father and most of my neighbours in digging that ore out of the ground!

For over 130 years, no other resource community in Canada has impacted the national news as often as Sudbury. Here is a very brief list of some of the issues that kept that community on the front pages of the national media:

• nickel was a metal that was absolutely critical in times of war and of primary concern to the nation and politicians. Sudbury nickel was essential for the allied cause in the Second World War and due to labour shortages Inco allowed women to work in the surface operations – they performed their duties admirably;

• government threats of nationalization when Inco was caught selling nickel to the Germans during World War One and the reason Inco closed a brand-new refinery in the U.S. and built one in Port Colborne in 1918, in the Niagara Peninsula;

• union battles during the cold war hysteria of the McCarthy era, which included car bombings, riots and government spying on the allegedly communist controlled mine mill union which was replaced by the right-leaning Steelworkers in 1962;

• a devastated local “lunar like” environment – Nasa astronauts visited the community in the early 1970s before going into space, however it was to study the geology not because Sudbury resembled the moon;

• some of the longest and most bitter strikes in Canadian history;

• very high death rates in the mines due to poor safety resulted in numerous high profile provincial public enquires during the 1970s and 1980s;

• massive layoffs and social disruption in the late 1970s and 1980s that encouraged the community to somewhat diversify its local economy;

• the largest global source of acid rain pollution – resulting in international condemnation – until the 1980s when new technologies significantly reduced sulphur emissions. The Copper Cliff superstack at Vales smelter will be coming down in a few years as there is not enough sulpher pollution to warrant its existence;

• a protracted foreign takeover battle during the last decade, which saw Brazilian- based Vale swallow Inco and Swiss-based Glencore takeover Falconbridge, when a proposed merger between the two Sudbury companies failed – just to name a few issues!

• Billionaire Leon Musk who founded the electic vehicle manufacturing company Tesla Inc. publicly pleads with miners to produce more nickel, a key component of the batteries he uses. Renews investor/public interest in this metal, Sudbury’s role in its production and reinforces link between mining and green manufacturing.

And let’s not forget the cultural impact of Stompin Tom’s “Sudbury Saturday Night” – “Well the girls are out to bingo and the boys are gettin stinko, We think no more of Inco on a Sudbury Saturday Night.” The song was first released in 1967. Allegedly, the management at INCO were so upset with the lyrics that they had local radio stations ban the song. Of course the song was an absolute hit with the workers. “Sudbury Saturday Night” is widely popular in Canada and will probably always be associated with the community even though the city has dramatically changed from those “rough and tumble” days. There is a bronze statue of Stompin Tom in front of the Sudbury Arena.

Politicians in both Queen’s Park and Ottawa should also remember and understand that Vale’s Creighton mine which started production in 1901, is still going strong 8,000 feet below surface. The deeper the company goes, the richer the nickel/copper and PGM content of the ore gets.

Meanwhile car manufacturing at Oshawa’s General Motors plant started in 1907 and unfortunately closed in 2018, dealing a devastating blow to southern Ontario’s auto-focused economy. Similarly, in 2011, Ford Motor Company permanently closed its St. Thomas assembly plant that opened in 1967. Now there are rumours that Ford may be closing its giant auto assembly plant in Oakville.

In fact, Northern Ontario’s mining camps have seen many mines whose lifespans have lasted 50 years or much longer while hundreds of others with shorter operations have still provided tens of thousands of jobs and billions in economic activity for the Ontario economy over the past century. So which sector is more sustainable, northern Ontario’s mining sector or the south’s auto assembly plants?

Sudbury today is a vibrant regional hub for north-eastern Ontario, with a thriving cluster of mining supply and service companies, post-secondary mining education and a centre of mineral research.

Successful revegetation initiatives have garnered international acclaim and the city continues to produce nickel, platinum, copper and cobalt – all key metals needed for the electrical vehicle markets – though I suspect we are probably going to wait a bit longer before nickel demand for batteries increases substantively and starts to significantly compete with the stainless steel market which is the primary user of this amazing metal.

That day will come and is probably causing Leon Musk some sleepless nights worrying if nickel shortages will cause manufacturing disruptions for his Tesla electric vehicles, hence his recent public statements urging global miners to produce more of this essential metal.

And to make one final point crystal clear to our political elites, there is still enormous quantities of poly-metallic ore to be found in the Sudbury Basin. It is at deeper depths as the easy big deposits have already been found.

The Basin is just making the geologists work a lot harder to find those deposits and I strongly believe we will still be digging that extraordinary resource out of the ground for another 100 years to say the least!

Stan Sudol is a Toronto-based communications consultant, freelance mining columnist and owner–editor of https://republicofmining.com/ He grew up in Sudbury and worked one year at the Clarabell Mill and spent an interesting summer underground at the old Frood-Stobie Mine.