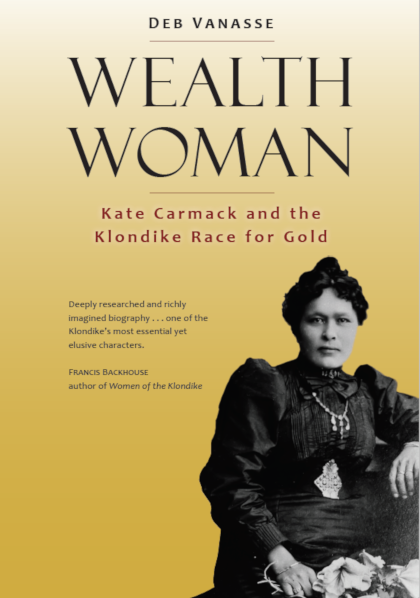

Kate Carmack was recently inducted into the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame for her part in discovering the Klondike gold fields. She is the first Aboriginal woman inducted into the Hall of Fame. Deb Vanasse has written the definitive story of Carmack’s fascinating life. It makes a terrific Christmas gift! Click here to order a copy of “Wealth Woman: Kate Carmack and the Klondike Race for Gold”: https://amzn.to/2yF7wZs

Deb Vanasse is an American writer of seventeen books, many of which are set in Alaska. She first became interested in the story of Kate Carmack when she hiked the “meanest miles” of the Chilkoot Trail, where as a young woman Kate packed for prospectors over the summit. After 36 years in Alaska, she now lives in Oregon, where she continues to write while doing freelance editing, coaching, and writing instruction. She is a co-founder of 49 Writers. www.debvanasse.com

Good Gold, Lotsa Gold – Excerpt from Chapter Ten

In addition to wealth, one of the key outcomes of what became known as “Discovery Day” in the Klondike—August 17, 1896—was a mosaic of stories that frame the event, dramas in which Kate plays various roles from supporting actress to chief protagonist, depending on the cultural context.

In the prevailing versions of the rush to gold in the Klondike, the heroes are rugged, independent, and irascible frontiersmen; women, if mentioned at all, serve to underscore the tension between adventure and domesticity as men explored and asserted themselves in the Frozen North. Where they could, the prospectors acquired and profited, the ultimate goal being to retreat from the wilderness to a comfortable existence improved by wealth.

Outside the Native community, most tales of the Klondike discovery feature George Carmack as the central figure, though in some, he is aided by Kate in the role of “Indian princess.” In one classically Victorian rendering, Kate keeps the gold a tantalizing

secret before eventually revealing it out of fear of losing her husband:

Still always uppermost in his [George’s] mind was the quest for the gold that he felt sure was not far away. Kate saw that this would sooner or later take her loved one from her, for with her young child she could not follow on all of the hard trips in search for the bits of metal that were her only rival in her husband’s thoughts. Why should she not tell him where the creeks were that ran for miles over golden pebbles?

That would make him happy and then, [once] he had all of it that he desired, he would stay contented at home with her and cease those tiresome wanderings for the metal whose lack made him so unhappy . . . She could not see him unhappy, and one day an excursion was planned that would lead them to the place where the mosses trailed over golden sands and the waters of the rippling creek looked like Chablis as they took alternately the color of the moss and gold on which they ran.1

In yet another version, the innocent play of Indian children becomes the providential clue that leads Kate’s husband to the gold. As the story goes, George Carmack, weakened and sickly, is rescued by “Skookum Charley.” While the “Eskimo” women tend to him in their “igloo,” their children play a game with rocks taken from a nearby stream. From the metallic ring of one of these rocks striking a steel pick, George recognizes that the quartz must contain gold. He traces the rocks back to their source, and the rush to the Klondike is on.2

Spread by newswire to papers throughout North America, the most outlandish of these discovery stories reads like a classic fairy tale. In it, Kate promises to show George where he can find gold on the condition that he pledge his love for her. Ostensibly

told in Kate’s own words—a curious mix of fake Indian-speak, romantic cliché, and terms Kate could not have known—the narrative reveals much about nineteenth-century American attitudes toward Natives, women, and wealth:

One night at dance in frozen country I first see white George. He talk to me and press my hand. He tell me how he walk about all over big, frozen country many, many months, and he tell me how he never find so much as one little piece of great gold which make white man’s heart glad.

Then he press my hand some more and love came into my heart and I remember some things I hear my brother Skookum Jim and my brother Tagish Charlie say. I think of what they tell me of a place where gold is as thick as the sand when one digs on the shore of the Meiozikaka, and I say: ‘Whiteman, meet me by the river at midnight and I tell you something to make your heart glad and love will come to you for Tagish Kate.’

White George he shake his head to show me he no believe Tagish Kate, but all same he came to river at midnight. I took him out in my canoe, away out in middle of river where no red man can hear and I whisper in white George’s ear: “I know spot where gold is thick like sand.” I tell paleface George he love me, me show him gold. He shake his head and say he no believe Tagish Kate.

Then I tell him how my brothers, Skookum Jim and Tagish Charley, have found place where they get heap much gold, and I tell him how they go and bring me back necklace all made out of little gold stones. When I see paleface George’s eye grow bright by light of moon and when he press my hand with his big strong hands I take one, two, three gold stones from under my dress and show them to him. George look at them and his eyes grow big. He swear he love Tagish Kate. I ask him if he make Tagish Kate his squaw. He says yes,

yes, many, many times. He take me in his arms; he kiss me and say he love me. Tagish Kate believes and is happy, very, very happy. Then comes wedding and plenty much to eat.

Now is September and in frozen country we must wait, wait for summer before we can go and find gold. Then me tell my brothers, Skookum Jim and Tagish Charlie, that my white chief George know where gold is. They very mad, but me, no care. Me love paleface George, my chief.

Then when summer came we make peace with Skookum Jim and Tagish Charlie, and one day all start together to place where gold is. Long, long time to get there. One day we came

to Rabbit creek and George he lay down and sleep. While he sleep I fill pan with sand and put it beside him. He wake up and see pan and wash out dirt and in it is gold all same like three dollars. George glad. He find heap much gold and love Tagish Kate and buy me heap nice clothes.3

In the age of yellow journalism, this was hardly the first fabricated story to make news, but it does complicate the matter of determining what part Kate actually played in the discovery that set off the rush to the Klondike. To add to the difficulty, there is no single clear and consistent explanation of the events from George Carmack himself that led up to his scratching a Discovery claim into the trunk of a birch tree near what became known as Bonanza Creek.4

Instead, what passes for George’s own account of the Klondike discovery is a heavily embellished tale that reveals more about the American sense of destiny, achievement, fortune, and individualism than anything else.

END