Kate Carmack was recently inducted into the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame for her part in discovering the Klondike gold fields. She is the first Aboriginal woman inducted into the Hall of Fame. Deb Vanasse has written the definitive story of Carmack’s fascinating life. Click here to order a copy of “Wealth Woman: Kate Carmack and the Klondike Race for Gold”: https://amzn.to/2yF7wZs

Deb Vanasse is an American writer of seventeen books, many of which are set in Alaska. She first became interested in the story of Kate Carmack when she hiked the “meanest miles” of the Chilkoot Trail, where as a young woman Kate packed for prospectors over the summit. After 36 years in Alaska, she now lives in Oregon, where she continues to write while doing freelance editing, coaching, and writing instruction. She is a co-founder of 49 Writers. www.debvanasse.com

Gold I Bring – Excerpt from Chapter One

The Roanoke is loaded with gold. Bags, cans, boxes, and crates cram its lower deck, jammed with a whopping ten tons of the precious metal panned and sluiced by lucky devils in the northern wilderness. Only a year ago, few had heard of the patch of low mountains and dense northern spruce now known as the Klondike. But these days, like an incantation of magic, the very word Klondike invokes abundance, the vindication of the American dream and the triumph of the individual in its most measurable manifestation: wealth.1

Nine days after setting out from the dreary and once sleepy port of St. Michael near the wide, muddy mouth of the Yukon River, the Roanoke chugs toward the dock of the North American Transport Company in Seattle, a city that enjoys a symbiotic relationship with the Klondike and its magic, the city having built

the magic and the magic having built the city. Four hundred fifty-eight passengers crowd the ship’s decks, eager for land. Sunshine seeps past clouds to light the throng gathered to welcome them and their gold: women in cinched-waist dresses and high, narrow hats; men in suits and suspenders, bowlers and derbies and straw tops.

Everyone wants to see who has gotten rich in the Klondike and who has returned empty-handed. In the Gilded Age of Horatio Alger and unbridled capitalism,

Americans are exhorted to industry, thrift, and temperance. No one can quite reconcile the idea of gold so easy and plentiful that you need none of these virtues to claim it. The idea is as unsettling as it is enticing, and on this day in 1898, there is no small amount of envy as the Roanoke steams for shore, especially when it comes to the scruffy common folk on her decks, the nouveaux made riches by gold.

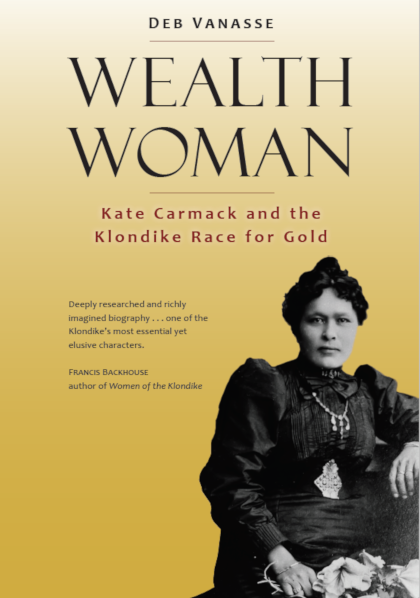

A particular challenge to American precepts on money, virtue, and class is the lone Indian woman on board the Roanoke, first called Shaaw Tláa, now called Kate Carmack. On her wrists and fingers, she wears gold, thin bands that belie her new and extraordinary wealth. With a firm, dark-eyed gaze, she meets

life head-on, grounded in the knowledge of who she is and from where she has come. Her features are soft, graceful; her resolve, unwavering. Possessed of a ready smile, she is resilient, resourceful, and strong—headstrong, even, with a temper.

Determined and accomplished, she has already adapted in remarkable ways to circumstances beyond any she could ever have imagined, but the challenges ahead will prove even more formidable.

Kate Carmack’s distinction—her claim to fame, as it were, though to her such a concept is foreign—is that she is thought to be the richest Indian woman in the world; since the extinction of the sixteenth-century colony for which the Roanoke is named, she is better situated with what passes for wealth than nearly any indigenous person of the United States or Canada has ever been.

As of yet, she knows nothing of those who’ve gone before her and failed, Indians such as Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse and Quanah Parker, who have only recently been consigned to a scrubbed-out existence on lands no one else wants.

The crowd gathered on this one Seattle dock exceeds twice again the entire population of Kate’s Tagish Indian band, of whom she knows each by name. Like all Indians of Alaska and the Yukon, the Tagish clans travel in yearly rounds, hunting caribou and Dall sheep, gathering berries, harvesting salmon, and trapping beaver and muskrat.

Thanks to the gatekeeping of their Tlingit neighbors, they have been among the last aboriginal people on the continent to confront head-on the object-driven culture of the West. They occupy the final frontier, some might say, although

the US Census Bureau in 1890 declared the American frontier more or less closed, and at any rate, when your ideas about land have more to do with proper use than with tightly defined boundaries, the whole idea of a frontier becomes pointless.2 Adapting is among the actions that have traditionally sustained Kate’s people, but there’s a tipping point between adaptation and assimilation that they’ve yet to fully test.

Her first language centers on verbs, her integrity tied to how well she protects, relates, negotiates, and adapts. In the form of luck, destiny comes to her; she does not seek it out. In Kate’s essence, her yaahei, which is Shaaw Tláa and not Kate, it is the journey that matters, not the end. The route is a circle, traversed with way-finding that demands close attention and behaviors that honor defined relationships.

In contrast, nineteenth-century Americans are a people of objects, their language driven by nouns. In their way of thinking, destiny requires pursuit; it is no coincidence that in their language, the words destiny and destination share the same root. They travel in lines, from point to point, toward tangible goals. They explore, they assert, they acquire. Among their most thrilling and coveted prizes is gold, of which Kate Carmack has quite a lot.

END