http://www.thesudburystar.com/

The Sudbury Basin is Ontario’s metallic equivalent to the Alberta oils sands without the massive open pits as most of the mines historically have been underground. For 135 years, the region’s unique polymetallic ore-bodies have produced nickel, copper and significant quantities of cobalt, gold, silver and platinum group metals (PGMs).

It is the third largest source of PGMs after South Africa and Russia. Many multi-generational families earn good middle-class salaries in the many mines, two mills, two smelters and one refinery. Roughly 30 per cent of provincial mining activity takes place in Sudbury, according to the Ontario Mining Association.

Glencore’s recent C$900 million investment in the development of its Onaping Depth project and Vale’s C$760 million phase one development of its Copper Cliff Deep mine are indications of growing confidence in the future of the region.

Vale has spent a little more than $1 billion on its Clean AER Copper Cliff Smelter project to lower sulphur dioxide emissions, which will be completed later this year while Glencore is spending $300 million to further reduce its sulphur output. Before these projects were started, sulphur dioxide emissions had already gone down about 95 per cent from 1970 levels – an astonishing success story of pollution abatement.

KGHM’s has still not committed to developing its Victoria deposit and rumors suggest it might be sold to an outside buyer while junior explorers like Wallbridge Mining Company continue to search the Basin for new deposits.

Geologist Peter Lightfoot is one of the most respected and internationally renowned experts on nickel. He has written the “quintessential bible” – a 680-page book titled “Origin of the Sudbury Igneous Complex” – on Sudbury’s globally unique geology.

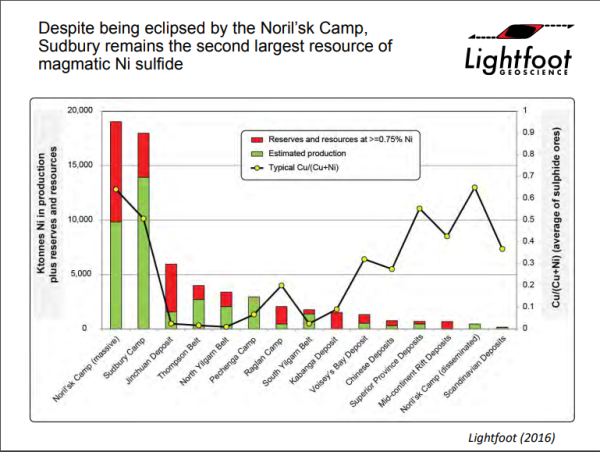

As Lightfoot’s graph on global nickel deposits shows, Sudbury and Russia’s Norilsk’s nickel deposits in Siberia are the two global nickel sulphide giants on the planet. All the other sulphide deposits dwarf these “gigantic sumo wrestlers of the nickel world. He feels that only 20 per cent of the ore has been found in the Sudbury Basin. The Sudbury mineralized deposits are widely thought to extend 10 km below the surface. The deepest mine in the Basin is Creighton, which is exploring the potential to eventually mine at the 10,000-foot level (3.04 km). Vale is currently mining around the 8,000-foot mark.

The Sudbury Basin is the richest mining region in Canada and depending how you measure the astonishingly rich gold deposits in Nevada’s Carlin Trend — could be the number one or two mining region in North America. We certainly have legitimate bragging rights.

The Sudbury mining ecosystem also includes a sophisticated mining supply and service sector, with 350 local companies, a number of them exporting to global markets, as well as supplying mines across the country.

Two colleges (Cambrian and Boreal) and Laurentian University provide post-secondary mining programs and a significant amount of research is being conducted primarily at the university –Mineral Exploration Research Centre, or MERC; Vale Living With Lakes Centre; Mirarco Mining Innovation; Centre for Research in Occupational Safety and Health (CROSH); and the independently run Centre for Mining Excellence (CEMI) and NORCAT.

In addition, the Bharti School of Engineering, the Harquail School of Earth Sciences and the Goodman School of Mines faculties provide a world-class post-secondary education for mining professionals allowing students to tap into Sudbury’s supercluster of mining production and innovation.

Of significant note, last year, the Metal Earth research program led by MERC was funded $104 million. This is the largest geoscience research initiative in the world.

The Silicon Valley of Mining

California’s Silicon Valley – south of San Francisco – is the most famous high-technology cluster in the world. Houston, Texas, has established itself as the leading cluster of oil and gas industries, services, research and educational institutes related to that sector.

Clusters are geographic concentrations of related companies in a specific field. They compete with each other, resulting in global innovation and the jobs of the future. Internationally known Havard professor, Michael Porter, has traveled the world advising many nations about the benefits of industrial clusters. In fact, almost 25 years ago, in a document for the Government of Canada, Professor Porter noticed Sudbury’s emerging mining cluster — it’s been years since I read the document, but seem to recall that it suggested the feds help it grow.

The Wynne government shamefully gave no financial support to the recently ignored Sudbury supercluster proposal, which was rejected by the federal government, purely on regional politics and probably a little prejudice — thinking that mining is a low-tech industry. Nothing can be further from the truth. Miners at Vale’s Tottem Mine carry Apple iPads in their lunch buckets. Many mines are transitioning to battery-driven equipment to eliminate unhealthy diesel fumes.

Laurentian professor Michael Lesher, Research Chair in Mineral Exploration, says, “mining is now one of the most technologically advanced industries in the world, utilizing state-of-the-art geophysical, geochemical, and satellite imaging techniques in exploration.”

In addition, telerobotics in mining, advanced motion-sensor technologies in mineral processing, sophisticated extraction technologies in metallurgical treatment, and state-of-the-art biological methods in remediation clearly show the extraordinary advances in this sector.”

The Toronto downtown Bank of Montreal building – the tallest skyscraper – is 72 stories high. The deepest mines in northeastern Ontario and northwestern Quebec are roughly equal to 650 stories underground. It takes an amazing amount of advanced technology to safely bring workers to those depths. A tidal wave of innovation is engulfing a new era of the digital underground.

The rejected super cluster proposal was going to improve environmental outcomes and increase productivity by tackling the challenges of water use, energy intensity and the environmental footprint of mining operations and position the country as a leader in mining and clean-tech solutions.

Considering the enormous benefits that mining research can provide the northern Ontario economy, the new Premier should adequately fund the following three research initiatives – perhaps from the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund Corporation:

– $40 million over four years for Centre for Mining Excellence (CEMI): For the past five years CEMI’s Ultra Deep Mining Network has been working on the development and commercialization of projects dealing with the challenges of deep mining. They focused on rock stress reduction, energy reductions and optimization, material transport and productivity and improved human health and effectiveness.

Ninety-three partners have worked on 25 projects that delivered 17 prototypes, eight products, nine IP protected patents, eight brokered deals resulting in 146 jobs. They are looking for more funding to continue their innovative research focusing on excavation stability and reliability, energy management for sustainable deep mining, mine production systems and the interplay of digital technologies and employee productivity.

– $40 million over four years for Centre for Mine Waste Biotechnology: Biomining allows industry to economically extract valuable minerals from mine waste while bioremediation can mitigate the environmental damage from mining activity by eliminating acid mine drainage or removing arsenic from old tailings. Molecular technology has advance so that specific microbes will be able to eliminate waste or mine certain minerals, some even in cold climates.

This proposed research institution would be the first in Canada and could potential resolve the legacy issue of thousands of abandoned mines and tailings areas across the country. It could possibly even be used by industry in the milling process to prevent acid material from reaching the environment in the first place. By commercializing these technologies, Ontario could become a world leader in clean mining.

-$40 million over four years for Mirarco Mining Innovation: For more than 20 years, MIRARCO’s five core research centres — safety research, geomechanics research, decision support software, sustainable energy solutions and climate adaptation — have provided the industry with quality applied research to manage risks in the mining sector.

Last April, Bruce Power donated $1 million to create an Industrial Chair position at Miraraco, which will highlight opportunities in sustainable clean energy solutions. One specific opportunity is for the development of Small Modular Reactors to generate clan, low-cost and reliable electricity in rural/remote regions.

Since 2013, the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund has provided more than $103 million for the growth of film and television production in Northern Ontario. These are largely short term projects that pay most of their staff lower wages. Ontario must start funding cutting-edge mineral sector research that will create new technologies and innovation for the mines of the future that will lead to potential export markets.

Creating the Harvard of Hardrock Mining

One of the best initiatives the provincial government ever did to develop the mining cluster in Sudbury was by transferring the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines and the Ontario Geological Survey to the city in the late 1980s.

During the Wynne era, a government report basically stated that “all universities can’t be all things to all people” and that they should start focusing on specializations that will enhance their global standing and further entice international students who pay much higher tuition fees. Considering the deficit financing of the past decade some merging or rationalization of duplicate university course was clearly needed. Nothing seemed to happen.

The new premier needs to revisit this issue and start with the consolidation and relocation – but not reduce the number of students or faculty – of all post-secondary mining engineering and geology programs to Laurentian University and establish a Havard of Hardrock Mining. That would entail the relocation of both the mining engineering and geology faculties of Queen’s and University of Toronto. In addition, there are currently 10 earth sciences/geology departments – aside from Laurentian – in Ontario’s 22 publicly funded universities.

Except for geology departments at Thunder Bay’s Lakehead University – closest to the Ring of Fire – and the one at the University of Windsor, which is focused on southern Ontario’s unique geology, the rest should be relocated to Laurentian. This would create a global centre of excellence in mining education due to the size and large number of academic experts in the mineral sector field.

One of the biggest problems that will prevent this from happening is that powerful university presidents will not easily give up faculties. The only way this will ever occur is if the new premier intervenes creates a taskforce of industry experts to start the transition in a non-disruptive manner.

The economic stimulus to the city of Sudbury, the significant enhancement of Laurentian’s reputation in the global mineral sector and the strategic enrichment of the city’s cluster of mining expertise all highlight the reasons for this consolidation to happen.

On a similar note, from the federal government, all mining research initiatives and staff from the Canmet research facilities and the mining section of the Geological Survey of Canada – both located in Ottawa – should also be transferred to Sudbury to enhance the economically significant mining cluster that already exists here.

Leveraging strategic minerals

Australia is the world’s largest producers of lithium, a key ingredient in the manufacturing of electric vehicle batteries. The state of Western Australia recently established a taskforce to investigate how that state can take full economic advantage of its strategic deposits.

Most industry analysts are predicting a massive conversion from gas-powered automobiles to electric vehicles over the next few decades.

No one is exactly sure on how fast this transition will take place, but it is coming. Electric vehicle batteries have huge amounts of nickel, as well as cobalt, copper, lithium and graphite.

There are basically two types of nickel deposits – sulphides and laterites. Sudbury, Thompson, northern Quebec, Voisey’s Bay and the future mines in the Ring of Fire all produce sulphide nickel.

Nickel laterites are subdivided into limonite and saprolite deposits. Electric vehicle batteries can only use the refined pure Class 1 nickel that comes from sulphides and limonites. Refined saprolite nickel (ferronickel) contains iron, making them perfect for stainless steel production – which is the main use for nickel today – but not for car batteries. And the very low-grade nickel pig iron, also used for stainless steel production, is not suitable for these batteries, either.

There are relatively few very huge nickel sulphide deposits in the world and battery makers are very worried there will be critical shortages of pure Class 1 nickel in the near future as the manufacturing of electric vehicles continues to increase.

The three of the five critical metals needed for the electric vehicle batteries – nickel, cobalt and copper are mined in the Sudbury Basin. The other two metals – lithium and graphite – are also found in various undeveloped deposits in Northern Ontario. Noront’s proposed Eagle’s Nest mine will produce nickel and copper. Nickel mines are generally found in clusters, so there is enormous potential to find more sulphide nickel deposits in the Ring of Fire.

A quick tangent about cobalt is also in order. Roughly 70 per cent of cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, a very politically insecure country with no rule of law, rampant corruption, very poor environmental standards and routinely use child miners.

All the car manufacturers of electric vehicles fear a shortage of all these materials. The new Ontario government should establish another industry task force made up of mining companies and car manufacturers to see how the province can leverage this strategic and politically secure source of raw materials, through security of supply, to ensure that the auto assembly plants stay in the province when they transition to the electric vehicle future.

The current President is vigorously lobbying for more vehicle manufacturing to be moved back to the U.S. In addition, the taskforce should analyze how Ontario can entice other car manufacturers to locate here like Nissan, Volkswagen and BMW with the possible security of supply of critical raw materials.

Stan Sudol is a Toronto-based communications consultant, freelance mining columnist and owner/editor of www.republicofmining.com

For the original source of this article: http://www.thesudburystar.com/2018/06/06/accent-sudbury-as-the-harvard-of-hardrock-mining

For Part 5 of 5: https://bit.ly/2AF54Cg