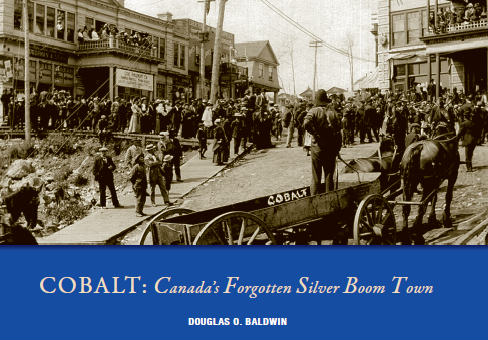

Douglas Baldwin is a retired history professor from Acadia University, Nova Scotia. This piece has been adapted from his new book, Cobalt: Canada’s Forgotten Silver Boom Town.

To order the book, click here: http://wmpub.ca/8094-SilverBoom.html

Speaking to the Empire Cub in Toronto in 1909, Rev. Canon Tucker told the story of a widely-travelled American who was asked where Toronto was. He thought for a moment, scratched his head and said, “Oh, yes, that is the place where you change cars for Cobalt.”

Although the value of the silver discovered in Cobalt far surpassed the riches uncovered during the Klondike rush only two decades earlier, few people today know of Cobalt’s history, or even of its existence.

Concentrated in an area less than thirteen square kilometres, about 400 kilometres north-east of Toronto near the Quebec border, Cobalt mines became the fourth-largest silver producer ever discovered.

When production peaked in 1911, Cobalt was providing roughly one-eighth of the world’s silver. During the First World War, the British government considered Canada’s silver supply so important to the war effort that it convinced Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden to use his influence to prevent a planned strike in the Cobalt mining camp.

The boom did not stop at Cobalt. Spreading out in all directions, prospectors discovered silver at Elk Lake and Gowganda and gold in Kirkland Lake and Timmins. Cobalt had exploded the myth that there were no important deposits of precious minerals east of the Rocky Mountains and encouraged further exploration of northern Ontario and beyond.

As the editor of the Journal of Commerce announced in 1913, Cobalt “added a new industry to the life of Ontario…. Attracted the world’s attention to Ontario’s Hinterland and advertised it more quickly than any other means.” These discoveries helped Toronto overtake Montreal as Canada’s financial headquarters.

RAILWAY WORKERS UNEARTH SILVER

The idea for a railway from Toronto to James Bay first emerged in 1884, but it wasn’t until the late 1890s that the provincial government began to take the idea seriously. A northern colonization railway would divert the growing flow of immigrants into Canada away from the prairies into New Ontario.

It would also slow the threatened flood of French Canadians into the area from north-western Quebec, and confirm Ontario’s ownership of the land. The purpose of the proposed railway was similar to the colonization roads of the 1860s that opened the region between the Ottawa River and Georgian Bay for farming.

Both were supported by Toronto businessmen eager to expand the city’s hinterland. When a prelimary survey of the area reported the possibility of finding valuable minerals, merchantable pine trees, and arable agricultural land, Premier Ross decided to build and operate a railway to the north. The Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway (T&NOR) became Ontario’s first public utility, predating Ontario Hydro by three years.

The Toronto financial and business community was delighted with the news. The president of the Board of Trade declared, “I believe it [T&NO] will prove of inestimable value in developing and settling the fertile wheat lands of New Ontario and the West – lands that are now practically valueless because of the want of railway facilities. Ontario and particularly Toronto will be the great gainers.”

Constuction commenced in October 1902. When work crews engaged in the construction of the T&NOR uncovered silver deposits the next year they touched off one of the most colourful and exciting mining booms in Canadian history. The editor of the British London Financier proclaimed that Cobalt was “the richest silver camp in the world and alone worth a journey to Canada to see.”

Here, he informed his readers, “it seems almost impossible to exaggerate … any urchin in the street could unerringly take the stranger to half-a-dozen mines and point to wonders which fairly beggar description.”

For three consecutive days in 1906 mounted police in New York City cleared Bond Street of expectant investors who were obstructing traffic in their efforts to buy Cobalt shares from the curb brokers. The word “Cobalt” was on every tongue. Visitors and prospectors came from around the world to inspect the area.

Electric light inventor Thomas Edison, hydro-electric baron and owner of Casa Loma Sir Henry Pellatt, ex-prime minister Wilfrid Laurier and future prime ministers Robert Laird Borden and William Lyon Mackenzie King, habitant poet William Henry Drummond (Cobalt’s first doctor), and the Prince of Wales were only a few of the famous and soon-to-famous individuals who caught “Cobalt Fever” and visited the mining camp.

COBALT AND THE GROUP OF SEVEN

After the mines’ supply of ore ran out, Toronto artists, Franklin Carmichael and A.Y. Jackson were attracted to Cobalt’s winding, hilly streets, deserted head frames, and abandoned mines. Cobalt’s landscape fit the Group of Seven’s conception of Canada. Carmichael’s water colours depicted the region in Northern Silver Mine (1930), LaRose Mine (1930), and Houses, Cobalt (1931-1932).

Frederick Banting, the co-inventor of insulin, also painted Cobalt — The Blue House and Cobalt Mine Shaft. Banting had served in the Canadian Medical Corps in the First World War and sought out A.Y. Jackson after the war to purchase a war painting. Based on their similar war experiences, enthusiasm for art, and fondness of the Canadian landscape, they formed a strong friendship and Banting often accompanied Jackson on his painting trips.

Together, they painted Cobalt in 1932. Yvonne McKague Housser was a founding member of the Canadian Group of Painters that succeeded the Group of Seven. She first discovered Cobalt on a student trip in 1917 and fell in love with the town’s unusual architecture and stark mining remains, which appeared like castles on a hill to her. Here, with fellow Torontonian and Canadian Group of Painters’ member Isabel McLaughlin, she painted Nipissing Mine, Silver Mine, Evening 1932 and Cobalt in the style of the Group of Seven.

THE STOCK MARKET

Toronto’s King Edward Hotel was the unofficial headquarters for businessmen interested in the Cobalt mining camp and its bellhops soon became accustomed to carrying heavy luggage filled with rock samples belonging to the weather-beaten prospectors checking in at the hotel’s opulent lobby. It was here in July 1907 that the Dr. Miller of the Ontario Bureau of Mines introduced the members of the American Institute of Mining Engineers to the richness of the ore.

One prominent Canadian mining engineer later remembered staying at the hotel when a prospector offered him several mines claims for $90,000 cash; “but as no reports had been made and no work had been done upon the property I naturally turned it down. That same property was sold within two hours for $140,000 cash, the deal being completed the same day.” The enormous interest in mining stocks created by the Cobalt boom resulted in the creation of the Toronto Standard Stock and Mining Exchange in 1908.

A prominent feature of the camp was the steady flow of dignitaries who arrived aboard the T&NO Railway’s parlour and pullman cars. In the fall of 1905, Premier J.P. Whitney and several cabinet members toured the district. The following spring the entire Ontario Legislature explored the area. In June, separate parties from New York, Montreal, Boston and Toronto arrived.

The hotels in the area were constantly filled to capacity as visitors continued to arrive in 1908. Members of the Toronto Stock Exchange arrived en mass in October — at one time that year there were as many as eleven carloads of brokers in Cobalt – followed by the Toronto Board of Trade. As the editor of the Journal of Commerce announced in 1913, Cobalt “added a new industry to the life of Ontario…. Attracted the world’s attention to Ontario’s Hinterland and advertised it more quickly than any other means.”

DISPLAYING THE SILVER ORE

The Ontario Bureau of Mines created interest in the area by displaying samples of the silver ore outside its Toronto office. It also contributed silver samples to the Canadian National Exhibition’s mineral exhibit to, as local MLA Frank Cochrane wrote to the Lieutenant Governor, “advertise the mineral wealth of this Province.”

The government purchased a 1,640 pound block of silver (the largest in existence) and exhibitted it in the provincial parliament building. The Bureau later donated a 34-inch block of silver ore to the Royal Ontario Museum. “This block…” the deputy minister of mines explained, “may never be equaled or excelled in the Province and if kept in a public museum it would be sketched and photographed and described and would pass into the literature and textbooks on Mineralogy and attract wide attention to the resources of the Provinces.”

As the number and size of the mines increased, the miners needed accommodations, food, clothes, and entertainment, and the mine owners required building supplies, mining equipment, hay for their horses, capital, and bunkhouse supplies. As a largest supplier of goods and services to the north, Toronto was a major beneficiary of the area’s expansion.

Arthur Coleman, professor of geology at the University of Toronto, told the Empire Club of Toronto, “There are plenty of houses in Rosedale, that have been paid for with silver from Cobalt…. I think you may say, without a particle of doubt, that the enormous spread of Toronto is very largely due to the filling up of the north with these mining men….A very large part of the supplies of everything that is used in the north comes from Toronto.”

AN EMERGING TOWN

In the midst of the mines, the town of Cobalt emerged out of the forest to serve the needs of prospectors and miners. The first arrivals believed that the silver would not last more than a year or two and thus built only temporary log or tar-paper shacks on the rocky terrain near Cobalt Lake. As silver production increased, the town quickly expanded from a stop-over and supply centre for the mines to a viable economic and social unit of its own.

The construction of better homes, retail stores and large commercial blocks, and the installation of sidewalks and sewers reflected the town’s progress. Tied to the south by a massive steel umbilical cord, Cobalt vibrated to the physical and psychological energies of the Toronto community. The Toronto press hired correspondents to write weekly accounts of the silver boom and before long there was a news bureau in Cobalt. Frank Mosure of the Toronto World was the first regular correspondent in the camp.

Cobalt merchants imported the latest fashions, fads, and equipment from Toronto. Stock brokers claimed to have a direct private wire to Toronto, Montreal, and New York. The creation of a mining stock exchange in Cobalt in 1906 and the establishment of six different branch banks promoted financial ties with Toronto and Montreal. Banks, mining companies, and churches were staffed by rotating career professionals with ties to Toronto, providing another link to the outside.

Following an outbreak of liquor-related lawlessness in the summer of 1905, Premier Whitney appointed Toronto Police Force detective George Caldbick as the first Provincial Constable in the newly-created Northern Police Division.

The Toronto Star wrote, “Armed with an unsullied billy, two pairs of shiny handcuffs, and a business-like revolver, ex-policeman Geo. Caudlbick [sic], the Ontario Government’s special limb of the law in Cobalt camp, departed for Northern Ontario today.” Four years later, the newly-created Ontario Provincial Police force chose Cobalt as the headquarters of one of its two divisions, and Caldbick became Divisional Inspector.

Less than a decade after the discovery of silver, Cobalt had a hockey team that played in the forerunner to the NHL, an Ontario Provincial Police station, an electric streetcar that linked the town with Lake Temiskaming fifteen kilometres farther north, a stock market exchange, the world’s largest compressed air plant, and was home to the Industrial Workers of the World’s first local in eastern North America. At one time there were approximately thirty-thousand people in the vicinity.

TORONTO-COBALT MONEY

Toronto money directly controlled the Trethewey Mining Company, the Temiskaming, the Beaver Consolidated, and the Cobalt Lake Mining companies. In 1909, the Montreal Star published a list of seventeen Canadians who had become millionaires thanks to their investments in Cobalt. Among this group were: David Dunlop, David Fasken, and W.G. Trethewey. The latter sold the Trethewey mine to Toronto Stockbroker J.P. Bickell for a million dollars.

In total, Trethewey probably netted ten million dollars from his Cobalt mines, some of which he used to build a family home in the wealthy Rosedale area of Toronto and a 600-acre model farm on the northern outskirts of Toronto in Weston. The roadway he built through the property is now called Trethewey Drive. David Dunlap used some of the money he made from the Cobalt mines to fund the construction of the David Dunlap Observatory – now in Richmond Hill – Canada’s largest optical telescope.

In 1904, David Fasken and several prominent New York investors established the Nipissing Mining Company on the east shore of Cobalt Lake. In addition to being president of the Nipissing, Cobalt’s largest mine, Fasken was also a substantial shareholder of LaRose Consolidated and the Trethewey Silver-Cobalt mines, and secretary-treasurer of the Chambers-Ferland mine.

In 1911, Fasken acquired the three Montreal River power plants that supplied Cobalt with hydroelectricity and merged them to create the Northern Ontario Light and Power Company Limited (of which he was president). David Fasken, lawyer, life insurance president, land developer, hydroelectric power magnate, and financier of the mineral resources of New Ontario, became one of the wealthiest men in Canada.

Sir Henry M. Pellatt was a Toronto financier and businessman who became best known for building Casa Loma. The Cobalt Lake Mining (1906) and the Mining Corporation of Canada (1916) provided the funds to build Casa Loma. Pellatt, who was also involved in a wide variety of businesses, from property holdings in Ontario, to insurance, transportation, timber, and banking, chaired companies that controlled a quarter of the Canadian economy.

THE FIVE-CENT PIECE

In 1907, when the price of cobalt fell from $3 to 0.37 cents, the Geological Survey of Canada suggested that this metal be used as part of the nation’s coinage. Since five cent coins were easily lost (the nickel was smaller than today’s and difficult to distinguish from the 10-cent piece), the Survey suggested that they be replaced by a larger coin made of cobalt. This metal, which was hard yet malleable, and didn’t tarnish, would not only absorb the surplus of cobalt, but be cheaper to produce. Eight years later, Thomas Gibson of the Bureau of Mines revived this idea.

He explained that a coin made of cobalt would be more attractive, difficult to counterfeit, and would “strike a chord in the national consciousness.” Since Canada was the chief source of cobalt, the coin would be distinctly Canadian and would provide needed employment. Whereas the American 5-cent piece was termed a nickel, this coin would be called “a cobalt”. The deputy director had some demonstration coins made and forwarded to Ottawa, but with no success.

COBALT TODAY

The First World War marked Cobalt’s last hurrah as the exhaustion of the ore bodies, and the increased production of low-grade ore raised costs and reduced earnings. Brief revivals in silver mining occurred in almost every subsequent decade.

When the price of silver rose sufficiently to make production profitable, abandoned mines were reopened, and rock dumps and tailing piles were re-examined. Agnico-Eagle Mines produced silver and cobalt from twenty-five properties between 1953 and 1989 until the silver was again depleted and Agnico-Eagle left Cobalt to focus on gold mining. Today, the demand for cobalt, which is used in lithium-ion batteries, has raised new hopes in the Cobalt and Toronto mining communities.

THE HISTORIC TOWN

In 2001, in a province-wide contest hosted by TV Ontario, three leading historians selected Cobalt as “Ontario’s Most Historic Town of the Century” for its role in establishing Ontario’s industrial economy. The following year the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada designated the Cobalt Mining District as a National Historic Site.

The next year the Royal Canadian Mint struck a commemorative pure silver dollar to mark the discovery of silver at Cobalt and Parks Canada unveiled two plaques in Cobalt declaring the “Cobalt Mining District” a National Historic Site, one of only three such “industrial historic sites” in Canada.

In recent decades, Cobalt has successfully parlayed government grants and private funding to promote its historical heritage. Large external wall murals illustrate the town’s past. Other successful history-based projects include the restoration of the Classic Theatre (1926-1973); an annual Miners’ Festival; and the Cobalt Historical Society’s interactive educational website (the Cobalt Adventure, 2010) that explores the town’s early history through historical documents.

Volunteers established a self-guided Heritage Silver Trail in 1985 that includes twenty attractions along a seventeen-kilometre loop. Cobalt’s rich history has also been commemorated by two parks landscaped with mining and milling equipment; a historical walking trail; a below-ground mine tour; the Bunker Military Museum; the Cobalt Northern Ontario Firefighters Museum; and the restoration of the town’s 1910 railway station (which shares the same architect as Toronto’s Union Station). In 2008 the Spring Pulse Poetry Festival was created to keep alive the memory of the north’s most famous poet, Dr. William Henry Drummond.

It is northern Ontario’s largest and only poetry gathering and piggybacks on the Dr. William Henry Drummond national poetry contest, the oldest such non-governmental poetry contest in Canada.As Cobalt’s official pamphlet, “Cobalt: Ontario’s Most Historic Town,” recently declared, “According to all accounts we should be dead, a ghost town like many of the former boom towns of the Old West. But we’re not dead, we’re just … rejuvenating, gathering our strength and our resources for the next round.” Toronto can’t wait!

To order the book, click here: http://wmpub.ca/8094-SilverBoom.html