Nickel Was the Most Strategic Metal

By anyone’s estimation, the highlight of Sudbury’s social calendar in 1939 was the visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on June 5th, accompanied by Prime Minister Mackenzie King and a host of local dignitaries. This was the first time a reigning British monarch had ever visited Canada, let alone Sudbury, a testimony to the growing importance of the region’s vital nickel mines. The nickel operations in the Sudbury Basin were booming due to growing global tensions and increased spending on military budgets. Sudbury and the northeastern Ontario gold mining centres of Timmins and Kirkland Lake were among the few economic bright spots in a country devastated by the Great Depression.

In an April 15, 1938 article, Maclean’s Magazine journalist Leslie McFarlane described the three mining communities as, “Northern Ontario’s glittering triangle….No communities in all of Canada are busier, none more prosperous. The same golden light shines on each.”

During the royal visit, precedence was broken by allowing Queen Elizabeth the first female ever to go underground at the Frood Mine. Traditionally miners thought women would bring bad luck if they were permitted underground. There were probably many who thought the beginning of the Second World War on September 1, 1939 was the result of her subterranean visit.

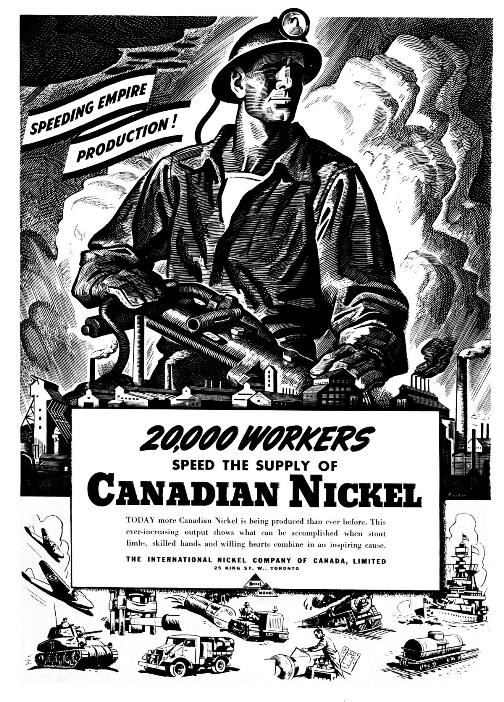

The German invasion of Poland was to have dramatic effects on Sudbury. Many communities across Canada, Britain and the United States played exceptional roles in producing certain commodities and munitions for the war effort. However, it would be no exaggeration to say that in North America, Sudbury was among the top few communities that were absolutely critical to the war effort. The International Nickel Company of Canada, as it was known back then, and its employees in Sudbury would go on to supply an astonishing 95 per cent of all Allied demands for nickel – a vital raw material and a foundation metal absolutely essential for the Allies’ final victory.

Nickel’s unique properties include a combination of strength, hardness, ductility, resistance to corrosion and the ability to maintain strength under high heat. It can transfer these properties to other metals making nickel a critical component for a wide variety of civilian and military products.

World War Two was a mechanized war that utilized more technically advanced equipment than ever before. To win, the Allied armies needed guns, tanks, planes, battleships and a host of other weaponry that could only be made from hardened nickel-steels and other nickel-alloys.

For example, in the mighty flying B-29 Superfortresses, thousands of pounds of nickel alloys were used ranging from oil cooling units and fastening devices to engine parts, exhaust systems, instrumentation, and control assemblies for guns.

The war in the Pacific was primarily an amphibious battle requiring rugged engines made from nickel alloy parts able to withstand the corrosive effects of salt water. Invasion landing craft, submarines and aircraft carriers contained various nickel steels like “Monel metal” in the hulls, propeller shafting, gas and water tanks, and vital valve and pump parts, just to name a few marine uses.

Nickel hardened armor plate for tanks, nickel alloys for anti-aircraft guns and ordinance and even lightweight, tough portable bridges used in the invasion of Germany all required this essential metal.

“Given the chance, Hitler would willingly have traded the whole Silesian Basin, and thrown in Hermann Goering and Dr. Goebbels to boot, for a year’s possession of the Sudbury Basin,” Maclean’s journalist James H. Gray aptly wrote in an October 1, 1947 article on the city.

From the beginning of the war, the company’s expertise and vast production and research facilities in Sudbury, Port Colborne, Huntington, New Jersey and Britain were at the complete disposal of the Allied war effort. Some of the British facilities and the Huntington rolling mills were sold in 1997 and 1998.

International Nickel facilities at complete disposal for allies

In 1939 American CEO Robert C. Stanley stated, “the first obligation of every corporation, as of every individual, is to give the utmost support to his Government in the prosecution of the war.” As it turned out, these were not empty words. Company profits actually declined approximately twenty-five per cent during the war years due to capital expenditures, war taxes and the use of more costly mining methods to accelerate the production of nickel, copper and platinum.

The price of nickel was under government control. From 1929 to 1941 nickel sold for 35 cents a pound. For the remainder of the war it was reduced to 31 ½ cents per pound. By contrast, the metal cost between 40 and 55 cents a pound during World War One.

The export sales of the company’s nickel, copper and platinum metals were made under Canadian Government permits and with the sanction of the British Government. The ultimate destination of all nickel products exported from Canada was strictly controlled by a system of warranties.

Nickel was one of the first metals to require allocation. Non-essential use of this strategic metal was banned which included most of International Nickel’s civilian markets.

Ironically, company scientists and metallurgists offered free technical assistance to over 14,000 American customers that the company worked so hard in the previous two decades to establish, to find substitutes for nickel. There were legitimate concerns that these customers would not come back after the war.

The 1943 Canadian victory nickel coin was no exception. Until the end of the war, the five cent piece was made from a copper-zinc alloy. In the United States, the five cent coin contained silver, a much less strategic metal than nickel.

Increased Nickel Production

In 1941 the Allied governments asked the company to increase production. International Nickel complied by committing $35 million to expand nickel output by 50 million pounds above 1940 production levels, reaching this goal by 1943 without any government subsidies. However, the Canadian government did allow the company to amortize within a five-year period, instead of ten or twenty years, $25 million worth of expansion expenditures.

That enormous task fell to American-born Ralph Parker, who at the time was the general superintendent of the mining and smelting division at Sudbury. It was one of Mr. Parker’s greatest achievements to organize the enormous program of enlarging the Sudbury mining and plant facilities without any loss of production.

To increase production of extraordinary war-time demands, Mr. Parker had to resort to “high-grading” which entails using above average ore grades and leaving behind lower grades that would have normally contributed to a longer, more profitable mine life. There was a real fear that the company would use up most of its reserves and have little to mine after the war.

Combined with an expansion program that would leave the company with excess capacity and labour, International Nickel’s actions demonstrated its commitment to the Allied war effort.

During the war about 40% of the Allies’ nickel came from the legendary Frood-Stobie open pit. However, with accelerated mining operations, it was evident that the mineral resources of the pit would be mined out ahead of schedule.

According to Inco archives five thousand jobs were created between December 1939 and April 1944 in a community with a population of about 32,500 in 1940.

Ralph Parker would go on to implement the use of aerial magnetometers in International Nickel’s exploration activities. The result was the discovery in Northern Manitoba of the Thompson ore body – at the time the second largest source of nickel in the western world. He has been honored in the Canadian Mining Hall of Fame for his many other contributions to Canada’s mining industry.

In the spring of 1940, the Sudbury Basin’s second largest producer Falconbridge Limited had its Norwegian refining facilities at Kristiansand overtaken by German invasion forces. For the duration of the war, International Nickel refined all of Falconbridge’s matte – an intermediate nickel product the needs further processing to produce the pure metal.

After invading Norway in April 1940 and taking over the Falconbridge refinery, the Germans also had access to the nickel mines at Evje and Flat, the latter being the largest nickel mine in Europe before the Petsamo operations were built. Germany also helped ease its own nickel shortages by seizing the nickel coinage of occupied countries.

C.D. Howe and the Fear of Labour Turmoil and Shortages

On a visit to Sudbury to promote the victory loan campaign in February 1942, the Hon. C.D. Howe, Canada’s famous minister of munitions and supplies, said, “Those of you who live in Sudbury and are employed by one of your nickel companies need not feel that you are not taking part in this war. … But I can say this, that if anything should happen to interrupt the production of nickel in the city of Sudbury, the whole character of the war will be changed. I know of no important munition of war that doesn’t have a nickel content.”

The other main reason for the visit was to ensure labour relations were harmonious. He wanted to avoid any labour disruptions as occurred at the very important aluminum refining centre in the Lake Saguenay region. A recent five day shutdown resulted in the considerable delay of airplane production in England and greatly reduced the stockpiles in the United States.

Labour shortages were a constant struggle during the war years. Hardrock miners from Kirkland Lake, Timmins and Sudbury who enlisted in the armed forces were in high demand for their expertise working with explosives – an integral part of the mining process. Canadian miners were used to blast tunnels and excavations in the Rock of Gibraltor to house medical facilities, repair shops, storage areas and defensive works. In the early fifties, Sudbury miners helped Toronto build its first subway tunnel.

In October 1941, wages were frozen by the federal government, the union leadership were discouraging strikes and many factory employees were routinely putting in 48 to 56 and even 64 hours per week.

The following March, the federal government established the National Selective Service (NSS) within the Department of Labour to help deal with the severe labour shortages throughout the entire economy due to the rapid expansion of war related industries and military demands on manpower. This initiative made it illegal for healthy males between seventeen and forty-five to work in any occupation deemed nonessential. These jobs included bartending, sales clerk, real estate agent and taxi drivers.

The first industry identified as an essential occupation was the nickel industry. Workers could not leave the employ of Inco or Falconbridge without the permission of a National Selective Services Officer. Hard-rock mining in the 1940s was a tough, dirty and dangerous job. Regardless of government regulation many men did leave for less strenuous jobs in southern Ontario that were also desperately short of workers.

In a 1979 pamphlet about his union organizing activities, Bob Miner wrote about working at Inco during the war, “Inco was a literal hellhole.…We were working under the damndest conditions I ever saw. A nickel mine is extremely hot. The rock gives off heat once it is broken. If you leave it broken for two weeks, you find is solid again and have to blast it. The temperatures are terrific. The rock is enormously heavy.”

Nickel workers in 1943 laboured for 56 hours a week with no overtime pay. They earned 51 cents an hour for surface work, 61 cents for underground labour while miners made 71 cents and first-class trades earned 78 cents an hour. There were no fringe benefits except a one week paid vacation.

From August 1942 to May 1943, Government initiatives had sent 4,159 new employees to the Sudbury mines yet in that same period 4,908 had left. When CEO Stanley wanted to reduce nickel production by ten per cent, the American government became involved in the labour problems expressing their series concerns that eventually caught the attention of Prime Minister Mackenzie King.

It was estimated that by 1943, 10 million pounds of nickel were being lost every quarter as a result of labour shortages. Various ideas to resolve this issue ranged from using prisoners to prosecuting violators of the National Selective Service regulations – many left the mines without the required permission – but ultimately none of these plans were adopted.

CKSO Radio Propaganda

The enormous war time demands for the metal ensured that the men working underground would be pushed to their very limits. For the ones who stayed at the mines, absenteeism was becoming a major issue. In the fall of 1942, the International Nickel Company of Canada sponsored a local CKSO radio program called “The Victory Parade.”

The following three radio spots were written by W.J. Woodill. The radio ads were used to encourage the general public to buy Victory Bonds as well as attempt to combat miner burnout with guilt.

“Mrs. Housewife! Are you one of those women who does her part by encouraging her husband to do his part in this war? Or are you “A Worry bird”, one of those girl friends of Hitler and Company? You know, even if that husband of yours doesn’t bring home a full war kit and rifle, he’s still doing his part if he’s doing his full eight hours of work every day. That Nickel or copper he’s turning out is mighty important these days.”

“Yes this is a critical time! Your husband is working not for so many cents an hour, but working for Victory. Working to put the metal into the hands of industry so there may be tools of war available. It’s vital that he does his job with his full heart in it. That husband of yours needs a clear head and his full attention to his job. Do your part, look after his health and his peace of mind. Remember he is needed on the job every minute of his shift.”

“That cheer of the crew is partially for you Mr. Miner, Mr. Smelter or Refinery worker. It’s also for the Nickel that makes the steel in the hulls of those shops stronger for the Nickel that gives the boilers the ability to stand the extra pounds of pressure. For the guns aboard that are stronger, more accurate, more reliable, thanks for the Nickel in them. It’s for the copper that goes into the electrical apparatus, it’s for the hundreds of tons of metal you are turning out for every branch of the armed forces. Yours is a mighty important job these days.”

But radio propaganda was not enough and the company had to turn to other groups of people that would ultimately save the day. In addition, due to the close working relationship between the Canadian federal government and Inco Limited, no one wanted to talk about the “elephant in the room” – the company’s notorious labour relations and anti-union activities.

American Gold Mines and Remember Kirkland Lake

The Americans had good reason to be upset with the labour shortages in Sudbury’s nickel mines. The United States entered the war after the bombing of Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941. By October of the following year, the War Production Board issued Order L-208 to suspend all gold mining in the United States. The gold mines were considered non-essential and scarce equipment and manpower were redirected to vital copper and iron ore facilities.

In Canada, the gold mining industry experienced a mini-boom at the beginning of the war to help pay for much needed American dollars used to acquire war supplies. With the passage of the Lend-Lease bill in the spring of 1941, gold mining became a non-essential industry. Production levels significantly decreased but a total ban on gold mining was not implemented on this side of the border.

The Canadian government hoped that unemployed Timmins and Kirkland Lake miners would migrate to the nickel operations only a few hundred miles away in Sudbury. Some came, however, wartime housing shortages and better working conditions in other industries kept many away.

For about three months in late 1941 and early 1942, the Kirkland Lake gold miners had witnessed one of the most bitter union strikes in Canadian labour history. The strike was largely over union recognition and ended in absolute defeat for the miners. “Remember Kirkland Lake” became a rallying cry for the country’s growing labour movement who wanted union legislation similar to the United States.

In 1935, as part of President Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Wagner Act was enacted.This progressive labour legislation protected the rights of most workers in the private sector to organize labour unions, take part in strikes and collective bargaining. It also barred employers from firing workers who particpated in union organizing.

As a result of the broad public support for the short-lived gold miner’s strike in Kirkland Lake and concerned about declining labour support, the Ontario Liberal government which was shortly facing a election, passed the Ontario Collective Bargaining Act, in April 1943. It was modeled on the Wagner Act and forced all employers in Ontario to recognize unions supported by the majority of workers.

Four months later the Conservatives won a minority government in the provincial election with the CCF – a left wing labour party – as the official opposition. Bob Carlin, a Mine Mill union organizer won the Sudbury riding with one of the biggest majorities in the province.

Finally on February 17, 1944, federal government, also worried about declining political support from labour and recent by-election losses, passed PC 1003 which mandated “compulsory recognition of trade unions with majority support.”

For the Kirkland Lake gold miners, the provincial and federal legislation came too late. War time priorities for base metal mines as well as declining gold reserves caused many of the mines to close. The workers scattered throughout southern Ontario where they helped organize unions in many different industries.

Inco and Falconbridge were wary of hiring the Kirkland Lake gold miners due to their union militancy. Both companies were severely criticized as “unpatriotic” in the union media for taking on only a small number of departing Kirkland Lake gold miners for fear of importing active union members.

Sudbury vital nickel mines and well paid workforce ensured that the community prospered greatly during the war years. However the rapid expansion and limited resources for any non war related activity like home building had its price. In December 1943 the community experienced a diphtheria epidemic due to the over crowded and poor housing conditions.

The Struggle for Union Organization

Before the war, among mining camps in Northern Ontario, Sudbury had earned the reputation of being a centre for “scabs” and “company stooges.”

Labour historian Jim Tester wrote in 1979, “Besides, they [Inco/Falconbridge] hated unions with a universal, almost pathological, passion.” He continues, “Inco had one of the best spy systems in all of North America, not exceeded by the notorious set-up at Fords. Inco’s reputation was known in every mining camp on the continent. In Kirkland Lake and Timmins there was a tremendous sympathy for the nickel workers of Sudbury. It was estimated that one in ten Inco workers was an informer.”

Inco hired people to intimidate union organizers handing out leaflets and disrupted meetings. The company even resorted to violence to keep the union out. In 1942, two union organizers were severely beaten and hospitalized and their downtown office destroyed by a group of twelve company goons. Although it was the middle of the day, no police were around to stop the violence. Two of the twelve went public and the union printed and distributed 10,000 leaflets throughout the community telling the truth.

A portion of the leaflet read, “This may be what INCO wants — it may be what the Star wants — but it is not what we want, and not what Sudbury wants. We are not going to stand for this kind of a deal. We are fighting for democracy abroad. We do not propose to accept fascism here in Canada and the above is plain Hitler fascism, and nothing else. … this is the violence that INCO and their blowzy prostitute “Sudbury Star” blame on the union.”

To forestall an independent union, Inco sponsored a company funded union called the United Copper Nickel Workers Union. The workers nicknamed it the “nickel rash.” There was also strong opposition to Mine Mill union organizing activities from the Catholic church, local police and media. The Sudbury Daily Star was often called the Inco Daily Star. William E. Mason, who owned the paper as well as the community’s only radio station CKSO was intensively anti-union and would use his media clout to rally against their organizing activities.

Robert Carlin, who came from the Kirkland Lake gold mines, was one of the key union leaders along with Bill Miner and James Kidd. A strong and determined organizing campaign finally won out and in December 1943, 6,913 men voted for Mine Mill while 1,187 voted for the company sponsored union the “Nickel Rash.” At Falconbridge, 765 men voted for the union and 294 against. By February 4, 1944 Local 598 of the Mine Mill and Smelter workers became the collective bargaining agents for Inco and by March 8th for Falconbridge.

Ultimately it was war time labour shortages, high taxes, wage controls and supportive provincial legislation – original federal laws were too weak and stronger legislation only came in after the certification – that allowed the union to finally become established in the Sudbury Basin. Sudbury was one of the least unionized cities in Canada at the start of the war and by 1950 the city had the largest organized workforce in the country who were among the highest paid.

In a speech in Butte, Montana, in November 1943, Mine Mill Chief, Reid Robinson praised the Sudbury workers but mentioned the Kirkland Lake strike, “Considerable credit for these extraordinary gains must go to our brave Kirkland Lake miners, whose courageous tenacity during the bitter strike in the winter of 1941 laid the groundwork for our organizational success in 1943. If these workers had not held their union together through unbelievable sacrifice, we could not of hoped for I.N.C.O.’s unionization today.”

Right from the beginning of the established union, communist leanings in some of the senior leadership started causing internal rifts and concern among high government officials in Canada and the United States. Federal government concern about communism in the union movement went back to the late 1930s and RCMP were routinely spying and infiltrating the union movement well into the early 1960s.

During the war, the Soviet Union was fighting with Britain, Canada and the United States against Germany, Italy and Japan, allowing the communist union members to be tolerated.

Once the cold war started in 1949, allegations against the union leadership of communist control would start more than a decade of inter-union rivalry, red-baiting, union raiding and violence in Sudbury that would make front-page headlines across Canada. For the moment, Sudbury’s nickel workers could take pride in finally establishing a union that would protect their hard won rights.

Women working for International Nickel

Since 1890, Ontario mining legislation had prohibited the employment of women in mines. Using its powers under the War Measures Act, the federal government issues an order-in-council on August 13, 1942 allowing women to be employed, but only in surface operations. On September 23, 1942, a second order-in-council was issued to allow women into the Port Colborne refinery.

Over 1,400 women were hired for productions and maintenance jobs for the duration of the war. They performed a variety of jobs such as operating ore distributors, repairing cell flotation equipment, piloting ore trains and working in the machine shop.

Twenty-one year old Elizabeth “Lisa” Dumencu, a resident of Lively, a Sudbury suburb, answered the call. “Women didn’t normally do this type of work, but we had to do our part,” she recalls. “It was really remarkable, but my husband Peter, worked even harder underground at Creighton mine.” She ran a 14 ore-car train and later became the first women to work in the machine and blacksmith shop, running a steam hammer. Lisa recalls that “the fellows in the shop treated me beautifully,” but adds that she often looks back on those days and asks herself, “However did I do this?”

Commenting about the role played by women in a 1946 speech, International Nickel Vice-President R.L. Beattie said, “Production of nickel and copper in sufficient quantities to assure an Allied victory would have been impossible had the women not stepped into the employment breach early in 1942, when labour was critically short, and the need for our products on the battlefronts steadily increasing.”

At the end of the war, the federal Canadian government rescinded the Order-in-Council allowing the employment of women in the company’s surface operations. International Nickel had a policy to save the positions for all former employees who joined the armed services so most of the returning men came back to work for the company. Nearly 500 soldiers, sailors and airmen from the region died on the battlefronts across the world.

American and British Rolling Mills and Refineries Played Critical Role

Like Falconbridge, French nickel producer Le Nickel was unable to refine its New Caledonian matte at its European refinery in Le Havre, France. International Nickel built a new facility at the Huntington, West Virginia rolling mills to process New Caledonian nickel.

The Huntington facility was among the most important in metal fabrication in the United States. Increased production pressures resulted in a strike in August 1944. Under an executive order of the President Roosevelt control of the plant was passed into the hands of the U.S. Army on August 29th and was not returned to the company until October 14th once all labour issues were resolved.

The Huntington works received many honours from the Army and Navy for excellence of performance in meeting war time manufacturing. This plant was one of 14 to be awarded an “E” flag when the honor was first established. By the end of the war, this strategic rolling mill was honored six times for the high quality and efficiency in producing ordnance equipment and special nickel alloys like Monel, Inconel and others. These specialty alloys, most invented at this facility, played an essential role in defense production.

During one of the award presentations, Rear Admiral W.H.P. Blandy, Chief of the Naval Ordnance Bureau, told the plant personnel that they “are in the Navy on shore duty.” In fact, all of International Nickel’s global facilities were mobilized for military production. The company strictly monitored the movement of nickel supplies to ensure none was diverted to unnecessary civilian production or smuggled to the enemy.

Rolling mills in Birmingham and Glasgow and refineries at Clydach and Acton, all in Britain were also an integral part of the war effort.

Roger Whittle’s Amazing Invention – the Jet Engine

The successful development of British-born Roger Whittle’s amazing invention, the jet turbine engine was integrally linked to Inco’s metallurgical expertise with high temperature nickel alloys.

In the early 1940s, at the request of Britain’s Air Ministry, company scientists worked furiously to solve the problem of appropriate materials for emerging designs in jet and gas turbine engines. The Germans were also working on their own version of a jet engine the Messerschmitt Me 262.

One of the most noted contributions during the war was the invention of a new alloy for jet-propelled aircraft engines by International Nickel metallurgists from the Henry Wiggin & Company Ltd. facilities in Birmingham.

This new alloy called “Nimonic 80” allowed the jet engine’s turbine parts, particularly the blades, to operate for long periods under tremendous stress, high heat and corrosive exhaust without deforming or melting. This new alloy was superior to German aircraft technology. The first British airplane outfitted with the new engine was the Meteor which first flew in 1943 and was finally approved for the air force in July, 1944.

The RAF Meteor squadrons were mostly used to counter the threat from the 7,000 V1 flying bombs that Germany fired across the English Channel at Britian. The Meteors could achieve a top speed of 480 m.p.h. This speed was fast enough to allow the Meteors to fly alongside the V1s and ‘knock’ them out of the sky by using their wing tips to flip the rockets on their backs.

After the war, the “Numonic 80” nickel alloy set the stage for a revolution in jet propelled aviation. Inco research scientists would go on to be responsible with the development of about 80 per cent of the specialized nickel-based super-alloys that are used in jet engines today.

At the time, the company was one of the globe’s leading copper suppliers. From the start of the war International Nickel supplied about 80 per cent of its electrolytic copper output for the British war effort. Its contract with the British Ministry of Supply kept being renewed annually during the war below world market price.

In the 1940s, International Nickel was also the world’s leading producer of platinum group metals, a byproduct of the Sudbury ores. Even today, the Sudbury Basin is still the world’s third largest source of platinum group metals after South Africa’s Bushvelt and the immensely rich Norilsk deposit in Russia’s Siberia. During the war, company metallurgists at the British Acton refinery developed superior platinum metal alloys that were used in airplane spark plugs, radar, bombing equipment and military explosives.

Australian Munitions Industry

At the beginning of the war, the Australian munitions industry was just beginning to develop. Traditionally, this sector depended on Britain for the nickel-hardened steels that went into ordnance production. With the fall of France and possible German invasion, Britain needed these high-grade alloys at home and stopped exports to Australia.

Australian troops fighting in the Middle-East were facing critical supply shortages for arms and ammunition. An Australian appeal to the Canadian Munitions and Supply Department in Ottawa solved the problem. Atlas Steels in Welland, Ontario, close to the Port Colborne refinery, started shipping the high-grade nickel-bearing steels to Australia.

Genreal Wavell’s troop’s successful campaigns in Libya were greatly aided by Canadian nickel steels. For the remainder of the war, ninety per cent of this valuable material used by the Australian munitions industry came from Canada.

Finland’s Strategic Nickel Deposits

In the 1930s, Inco had invested several million dollars developing valuable nickel deposits in the Petsamo district of northern Finland, close to the Russian border. At the outbreak of war events in the region unfolded with lightning speed. The Soviets invaded Finland and annexed the nickel mines in March 1940. Germany invaded Russia in 1941 and the Finns recaptured the nickel mines which were immediately put under German control.

The British wanted Inco Limited to keep operating the mines even though production would be sold to the Germans. They were hoping that Inco could slow down development and provide the necessary intelligence for nickel shipments that the British navy could destroy. The Mackenzie King government in Ottawa steadfastly refused to co-operate with this plan. Their big fear was the negative public reaction if it was discovered that a Canadian company was helping send vital nickel to the enemy.

During the First World War some Sudbury nickel had been shipped to the Germans via a neutral United States. The “Deutschland” incident caused a huge uproar in Canada and Prime Minister King was adamant that a similar event would not happen. Inco was caught in the middle but agreed to abide with the Canadian government even though its concession in Finland would ultimately be lost.

By the end of that year, about 70,000 tons of nickel was shipped back to Germany from Petsamo. In 1944, the tides of war were changing once again and the Finns signed an armistice with Russia in September. The Germans fought bitterly to keep control of the vital nickel mines.

At the end of the war, the nickel mines of northern Finland were annexed by Russia and Inco was eventually paid $20 million as compensation even though CEO Robert Stanley felt this was $15 million less than its worth. The Soviets changed the name Petsamo to Pechenga and the operations are still in production under Norilsk Nickel’s control. Inco Limited had helped establish the Soviet Union’s nickel industry that eventually became a significant competitor and cut into the company’s global market share in the 1980s and 1990s.

International Nickel Communities Should be Proud of Their Wartime Roles

There was a decrease in nickel consumption immediately after the war. However, the rebuilding of the world’s devastated economies and pent-up civilian demand for nickel containing products combined with the military build-up during the Korean conflict and ensuing cold war hostilities, ensured exploding demand for this strategic metal. Further exploration in the Sudbury Basin found more deposits that helped meet growing world demand.

From 1939 to 1945, International Nickel delivered to the Allied countries 1.5 billion pounds of nickel, 1.75 billion pounds of copper and over 1.8 million ounces of platinum metals. The tonnage of ore mined during the war years equaled the production of the company and its predecessors during the previous 54 years of their existence.

On May 17, 1943, a live Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Radio broadcast from Sudbury announced, “ The ships, guns, tanks and planes that today are taking parting a victory which in our hearts makes us proud and grateful, have been lightened , strengthened or toughened by nickel mined here. …. And every minute of every day, the nickel produced by the men and women in our audience tonight, toughens and multiplies the sinews of war that will help spell the annihilation of the Axis forces. Here, then, their task is tremendously vital, and their record – a distinguished one.”

By the beginning of the Second World War, International Nickel Company of Canada was a global corporation with operations and markets in Canada, the United States, Britain and Europe. Other than an intrinsic anti-union sentiment pervasive throughout Inco management – very common amongst all large corporations of the era – the company made significant financial sacrifices for the war effort.

The company gave up lower grade ore reserves to speed up production, worked closely with Canadian government officials to ensure no nickel reached enemy nations, over built capacity that might not have been needed after the war and helped customers find substitutes for nickel, not sure they would come back to the original metal.

The company even gave up the Petsamo nickel concession, the largest new nickel deposit in the world at that time for political reasons and inadequate compensation. The company’s loyalty to Canada over its broader corporate interests would surprise many even in this day and age.

This lengthy essay was originally published in 2006.