To order a copy of Call of the Northland: Riding the Train That Nearly Toppled a Government, click here: http://www.northland-book.net/buy.html

Historian, author and photographer Thomas Blampied has been interested in railways for as long as he can remember. Growing up east of Toronto, he spent summer evenings sitting trackside with his father watching streamlined VIA trains race past and long freight trains rumble by. From these early railway experiences grew a lifelong passion for railways and rail travel which has manifested itself through model railroading, photography, writing, railway preservation and the academic study of railway history. This is his fourth book about railways in Ontario. He has studied in both Canada and the United Kingdom and currently resides in Southern Ontario.

Chapter 1: First Steps to the North

The day of the trip: before dawn. Up around five, I was packed and ready to go. My journey would take two trains: one west into Toronto and then one north to Cochrane. I had some breakfast, never much on travel or photo days, and got a ride to the Whitby Station. It was a cold and drizzly morning in late April as I waited on the platform for the 6:18 GO train to Toronto. I must have looked odd, standing with all my bags and winter coat in the rain, among the latest spring fashions.

The train arrived and I boarded with the commuters – all of them pushy and determined to have their seat. As usual, I sat up behind the crew, but was disappointed to see that the window separating the crew and passengers had been boarded up. I had liked looking through this window for years as I could see the track ahead from the crew’s point of view.

The weather did not improve as we rolled along the GO Subdivision (the operational name for a particular stretch of track, a subdivision is often referred to as a Sub), running parallel to Highway 401. The 401 is the busiest and most congested highway in North America and cars were crawling through the rain as we passed them. We joined CN’s Kingston Sub just west of Pickering and turned south towards Lake Ontario, invisible in the pre-dawn shadows. As usual, the train was crowded and my bags had to be perched on my lap and between my feet to make room for others.

About an hour after leaving Whitby, we arrived at Union Station – Canada’s busiest railway station and one of Toronto’s grandest spaces. The platforms were under a dark train shed, dripping from the morning showers. Even the Great Hall, my favourite place in all of Toronto, with its magnificent arched roof and stonework, was unusually dark in the rainy gloom.

A few weeks earlier, on April 13 (a Friday!) I had been to Union Station to buy my tickets for the trip. As I arrived, the young woman at the Ontario Northland (ONR) desk was putting up a red stop sign, which proclaimed “Ontario Northland NOT For Sale!” in large white letters. This sign was the symbol of the fight, the recognizable emblem used by everyone opposed to the sale. I bought my ticket and she handed me a brochure outlining the issues surrounding the proposed sale of the Ontario Northland Transportation Commission (ONTC – for most of this book, ONTC and ONR are used interchangeably). We talked about the sale – she was worried about the people who would have to find another way to travel south for medical appointments, a routine part of northern life.

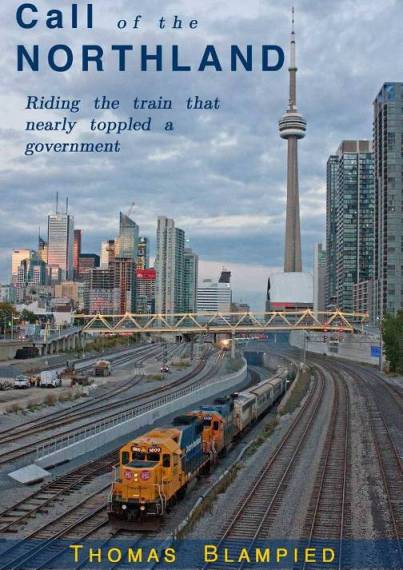

I said goodbye and went on to my other errands in Toronto which would take up the bulk of the day. That evening, my errands complete, I was standing on the Bathurst Street bridge, waiting to photograph the southbound Northlander as it headed for servicing at VIA Rail’s Toronto Maintenance Centre after its journey from the north. The train was early and as it raced under the bridge, I saw that it too had a NOT For Sale sign, right on the front guardrail of the freshly painted locomotive. To Ontario Northland, the sale (or “divestment”) was the latest assault on its whole way of life.

The Ontario Northland ticket desk was quiet that rainy late-April morning. There were no customers when I passed it, but the NOT For Sale sign was still clearly displayed, just as it had been earlier in the month when I had talked with the ticket agent. Since I’d already bought my tickets I headed straight to the departure gate, wondering about what I might see over the next few days.

This is the story of a railway journey covering nearly 500 miles from the monotonous suburbs of Toronto to the rugged wilderness of northeastern Ontario, and of the politics and history that compelled me to make it. It isn’t the most arduous journey, but it is one that has now been lost. From coast to coast, the story of railways in Canada always seems to be one of loss: miles of track ripped up; trains cancelled; whole communities losing a lifeline to the rest of the world.

Except for a few metropolitan pockets investing in commuter trains, the current state of Canadian passenger railways is pitiful. As the main freight carriers expand traffic on key arterial routes, branch lines are abandoned. Outside of Ontario and Quebec, VIA Rail service is routinely scaled back in an effort to cut costs. This was a journey to capture something before it was gone, before it became just another chapter in the decline of the steel ribbons that united Canada over 125 years ago.

On March 23, 2012, the Ontario government announced that, due to increasing costs, they would begin the divestment of the ONTC, axing some services and selling off the rest. I was busy painting my room when the announcement was made and I only learned the news a few hours later when my uncle sent me an online article about it. I decided on the spot to bring forward my dream trip to the north. To be honest, I knew very little about the Ontario Northland Railway. The ONR had always been a presence in the background of my railway-obsessed mind: it was a link to northern Ontario, I liked its paint schemes and it had interesting routes running to remote communities. In fact, I had started a model railroad of the ONR in HO scale only two weeks before the announcement. I had often dreamt of riding the iconic Northlander from Toronto to the ONR’s northern hub of Cochrane, a small railway town northeast of Timmins, surrounded by trees, lakes and empty space. I had resisted the call of the northland for years, but I could resist no longer.

What was this call? It’s rather hard to explain, but my understanding of it grew as I travelled and researched this book. There is something built into Canadians that kicks in at the first snow and remains with them through the winter. It is a state of being – a reassured stoicism in the face of the bleak and cold season. It is in the people, not the place. In recent years, I have spent much of my time in the north of England, which often gets at least one snowstorm each year. But while people there always struggle with the white stuff, I just keep going as if it were a normal occurrence. When it snows in England, it makes me think of home and the stillness after a fresh snowfall.

There is also a pull to the north; something primal, powerful. Renowned actor Christopher Plummer talked of it during a Canada Day speech in 2010 as he recounted how Canadians around the world always feel a twinge of longing for the northern expanse of their homeland, while acclaimed writer Margaret Atwood has lectured about the “hypnotic” draw of the north.1 It predates the country we call Canada as it infected the earliest European explorers who were overwhelmed by the new and rugged land they saw before them. Even before European contact, Native legends told of the dangerous spirits inhabiting lethal winter storms, ready to prey on the careless and the lost.

When I visited Ottawa a few years ago and took in the Mosaika light show on Parliament Hill, what struck me most during the show were the sounds of a loon call, geese and a howling wind – the sounds of the north. It permeates your entire being and calls you forward – northward. The north in Canadian lore is still wild, untamed, and it can make you go mad. Stephen Leacock called it “Bush Mania” and the government’s announcement about the ONTC had given me a good case of it.2 My chance to head north had come; the government had compelled me to travel before the train no longer existed. The Northlander was to be cancelled outright, not even put up for sale. Time was limited and I had to act now.

Almost immediately following the announcement, groups of people came together and formed organizations to fight the government’s plan. Unions worried about jobs, communities worried about the potential loss of transportation links and people feared losing their connection, literal and symbolic, to the rest of the world. I too started publicizing the issue, albeit to a modest online audience through my website.

But what was this way of life now under threat? I had travelled on the Northlander once before, but only as far as Gravenhurst, which wasn’t really north at all. Cochrane, the northern terminus of the ONR’s passenger train from Toronto, was north. Or was it? The town lies almost exactly on the 49th parallel which, if you look on a map, is the southern border of Canada’s western provinces. In a sense, all I would be doing was connecting with the rest of Canada for the first time in my life. I was under no illusions. I knew this wasn’t a land of igloos and coureurs des bois, but I didn’t know what it actually was either. It was rural, mostly empty, rough, impoverished and would probably go well with Gordon Lightfoot’s or Neil Young’s mournful ballads.

What I did know for sure was that, without the railway, there would be no north as I knew it. Rail was the first viable transport northward as canoes couldn’t be made large enough to carry sufficient supplies for towns, and roads hadn’t yet been built through the rocks, swamp and dense forests. In fact, many places in the north still don’t have vehicular access. It was only in 1902, with the Temiskaming & Northern Ontario Railway (T&NO) that the north we think of today could truly begin. Before then, only a few traders and numerous First Nations settlements – mostly Cree – settlements populated this vast region.

Over time, the T&NO evolved into the ONR of today. It is a remarkable story and certainly worth learning and sharing. This book tells the story of how the T&NO opened up the north to development, how Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty’s government tried to put an end to the ONTC and how I came to experience the north when I discovered it for myself during a late April snowstorm in 2012, 110 years after the railway began. This is an account of the railway, the land it serves and the events that nearly put an end to it. It is also about one curious individual’s first encounter with the north and what he saw there.

1. Margaret Atwood, Strange Things: The Malevolent North in Canadian Literature (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995).

2. Stephen Leacock, Literary Lapses, (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1993).

END